In this week's Queen's Speech, Her Majesty announced that her

Government (and I suspect that she would rather they were not her Government),

intended to introduce legislation that would require voters to produce photographic

ID at Polling Stations in order to vote at general elections and English local

elections. Predictably, this provoked much opposition on the twin grounds that

it was a “blatant attempt by the Tories to rig the result of the next general

election," (Cat Smith, Shadow Minister for Voter Engagement and Youth

Affairs), and that it would disenfranchise thousands of people, because, as Darren Hughes

of the Electoral Reform Society (ERS), said “these plans will leave tens of

thousands of legitimate voters voiceless”.

According to The Independent, a Cabinet Office spokeswoman

said: "Electoral fraud is an unacceptable crime that strikes at a core

principle of our democracy." But, isn't potentially disenfranchising

thousands of people even more of a threat to democracy? The answer really

depends on how much of a problem electoral fraud actually is. Personation -

that is 'assuming the identity of another (person) in order to deceive' - at

the ballot box is extremely rare; during 2017 there were 336 cases of alleged

electoral fraud and only one of those was for personation at a Polling Station,

while there were two for a similar offence relating to postal votes. While the

majority of alleged offenses resulted in no action being taken, in 165 cases

where action was necessary, these were all alleged campaign frauds, and nothing do do with voters.

Cynics might say that these low numbers do not prove that

there is little or no electoral fraud, as there are (obviously) no numbers for

how many frauds have been successful and undetected. The Metropolitan Police's

much criticised investigation into electoral fraud in Tower Hamlets in 2014,

following which former mayor Luftur Rahman was found guilty of corrupt and

illegal practices, suggests that we should take these figures as advisory

rather than absolute. Nonetheless, they do imply that the scale of the

problem is minuscule and that the Government's proposals are taking the

proverbial sledgehammer to a microscopic nut.

One might imagine that assessing the scale of the problem vis a vis voters potentially disenfranchised

by requiring them to produce photo ID at Polling Stations would be difficult, but it is actually easier than one might imagine. In 2015, the Electoral Commission

said that about 3.5 million electors did not have an acceptable form of photo

ID, and in May this year, a trial at local elections in ten areas across the country where voters were required to produce photo ID found that 819 people

were turned away from Polling Stations for a lack of such ID.

None of the 819 subsequently returned to vote. The net result is that in a

limited number of constituencies, at one election, the number of people unable

to vote for lack of photo ID was more than double the number of cases of

electoral fraud in the whole of 2017, and more than 270 times the number of

instances of personation in that year.

|

| It's not compulsory to take a dog to a Polling Station... |

On the face of it, those numbers suggest that requiring

voters to produce photo ID - especially when so many people have none - is

deeply undemocratic since the risk of fraud is so greatly outweighed by the

risk of disenfranchisement. To mitigate that risk, however there are proposals

that anyone lacking photographic ID would be able to apply for a free document

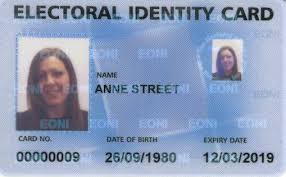

proving their identity. This is already the case in Northern Ireland, where

along with the usual form of photo ID that can be used - passport, driving

licence, bus or rail pass, among others - the local Electoral Office issues an

electoral identity card, which serves the dual purpose of authenticating voters

and providing proof of age when the holder wishes to buy age restricted

products such as alcohol and tobacco. This scheme was introduced in 2002 and

has improved public confidence in the electoral process and reduced instances

of suspected electoral fraud. The number of registered voters in Northern

Ireland declined in 2002, with the number of voters turned away because someone

had already voted in their name, and of people voting under more than one name both

falling. This certainly suggests that requiring photo ID reduces risk of fraud,

but that may only be because the instances of fraud were higher in Northern

Ireland than those on the mainland in the first place.

Compulsory - or even voluntary - identity cards are

something that, in general, the British public views with some suspicion. The

Identity Cards Act of 2006 proposed a national identity card that would serve

as a personal identification document and European Union travel document. There

were objections on the grounds of cost, effectiveness, and data protection.

Given the amount of data that would have been harvested and subsequently stored

in the associated National Identity Register (NIR), and especially in view of

successive government's track record on major IT projects, these concerns were

probably well-founded. The scheme died a slow death and the Identity Cards Act

was repealed in 2010 and the NIR database destroyed.

While photo ID may not be compulsory in the UK (yet), life

without it can be inconvenient at best. If you want to rent a flat, apply for a

job, open a bank account, or take a domestic flight, you'll need photo ID, and

apart from buying an alcoholic drink, many pubs and most clubs now want photo

ID just to get through the door. And, if

like me, you want to go to the BBC to see a radio show recorded, you'll need

photo ID for that too.

|

| In England and Wales, 76% of the population hold a passport. |

If - and it's a big if, given the fact that we currently

have a minority Government and a General Election within the coming months is

quite probable - legislation passes to require voter ID, I would seriously hope

that all of the 3.5 million people lacking such ID apply immediately for

whatever state-issued ID the Government proposes, and for two reasons. Firstly

- and obviously - to prevent those people from being disenfranchised, and thereby

allay fears of any future election being 'rigged' (beyond the not unreasonable

concern that campaign methods might be achieving that outcome anyway, although

that is a whole different bouilloire de

poisson), and secondly to watch the carnage as an under-prepared government

department using an inadequate IT system goes into complete meltdown trying to

cope with a tsunami of applications.